Terminal State vs. Intrinsic Value

“… it is not enough to think problems forward. You must also think in reverse, much like the rustic who wanted to know where he was going to die so that he’d never go there.” – Charlie Munger

Every so often, someone gives voice to an idea you’ve been wrestling with for years, and the scattered thoughts snap into focus. This essay unpacks one such idea that steered me towards a first-principles approach to valuation.

I was recently introduced to the work of Utpal Sheth, an Indian investor who worked closely with Rakesh Jhunjhunwala. Jhunjhunwala’s record of compounding is legendary, reportedly starting in 1985 with about $500,000 and growing it into more than $6 billion by 2022, the year of his passing. Utpal has carried forward that mantle, championing their process. If you have an hour to spare, que up one of his recent talks; it’s well worth the listen.

One of their core tenets is what Utpal calls “Terminal Value Investing”. He outlines his perspective and process in an exceptional presentation. Rather than reprise the full framework, which is well worth studying on its own, I want to focus here on the psychological shift: evolving from a think-forward approach to valuation toward a think-backward approach.

Terminal Value to Terminal State

Anyone who has slogged through finance courses or built DCF models recognizes the terminal value as the final line in a stream of projected cash flows. As Investopedia defines it:

“Terminal value (TV) is the value of a company beyond the period for which future cash flows can be estimated. Terminal value assumes that the business will grow at a set rate forever after the forecast period, which is typically five years or less.”

Tellingly, it adds:

“Terminal value often makes up a large percentage of the total assessed value of a business.”

From here, finance textbooks immediately pivot to formulas.

But there’s a crucial distinction between building financial models and building mental models. Terminal value, as typically taught, is an extrapolation exercise. Terminal State, by contrast, is a mindset shift. It reframes how we think about time, probability, and the economics that drive long-term compounding.

That’s why I have found a useful reframing, evolving from “Terminal Value,” to “Terminal State[1].”

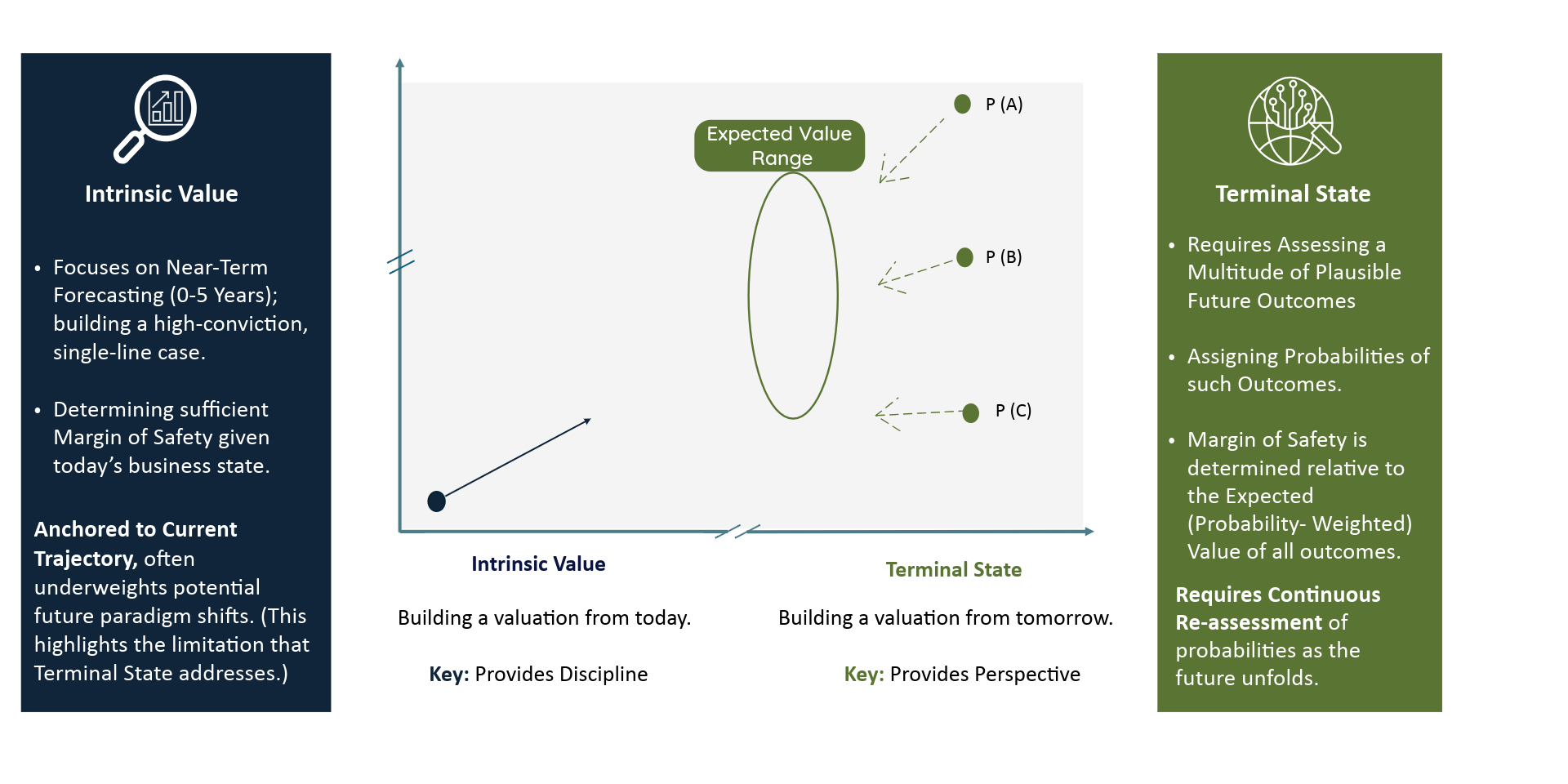

Terminal State vs. Intrinsic Value

When evaluating any asset, whether gold, real estate, a private business, a listed stock, or a bond, the task is the same: determine what the asset is worth. Market quotes tell you only what others will pay today; but the investor’s job is to decide whether that quote is a useful signal of the underlying value.

There are many ways to answer the valuation question. The classical route for many value investors is to calculate intrinsic value.

Intrinsic Value: The Problem-Forward Frame

The term intrinsic value has been in the investing lexicon for almost a century. Benjamin Graham and David Dodd described it as:

“that value which is justified by the facts, e.g., the assets, earnings, dividends, [and] definite prospects, as distinct, let us say, from market quotations established by artificial manipulation or distorted by psychological excess” (Graham & Dodd, 2008, p.64).

In practice, intrinsic value has historically been applied in two broad ways:

· Asset-oriented: net assets, liquidation values, and “net-net” style conservatism that dominated the Depression-era playbook.

· Earnings-oriented: discounted future cash flows, earnings multiples, and the stream-of-benefits approach that Graham’s followers evolved toward after markets recovered and cash-generative businesses became more prominent.

Psychologically, intrinsic value is usually anchored to today: you take present facts and expectations and push them forward. You start from now and build out margin assumptions, growth rates, and terminal multiples, arriving at a forecast of future cash flows that you discount back to a present value that either justifies or doesn’t justify the current price.

This is a fine and rigorous approach. But it implicitly emphasizes the path from today to tomorrow, often anchoring disproportionately to near-term estimates.

Terminal State: The Problem-Backward Frame

Terminal State reverses the vantage point. Instead of projecting outward from today, you start by imagining a credible future state of the business or asset and work backward.

What does the business look like in 5, 10, or 20 years (or even 150 years – more on this below) if it thrives?

What will the industry economics be?

What portion of those economics is the business likely to capture? Put differently, is there a differentiator enabling the business to grow and/or maintain market share?

From there, you assign probabilities to those futures and value the expected terminal outcome.

At its core, Terminal State is scenario-based and probability-weighted. Rather than building a single, best-guess, multi-year forecast, you build a set of plausible end-states and estimate how likely each one is.

Mental Model: Intrinsic Value vs. Terminal State

The psychological shift is crucial: Terminal State forces you to ask questions about the mature state of the business, not whether next quarter’s numbers will miss or beat expectations. It compels the investor to test the long-run durability of competitive advantages, capital allocation decisions, and the industry’s underlying economics.

Much like solving a child’s maze puzzle, envisioning the end-state and working backwards provides a much clearer view.

As a screening tool, it’s invaluable, if the future is too cloudy, move on to businesses with more predictable outcomes. Cloudiness may stem from intense competition (low barriers to entry), disruptive technological shifts, or other structural headwinds.

Charlie Munger (and Coca‑Cola): a masterclass in terminal thinking

Charlie Munger’s recounting of the Coca‑Cola opportunity is the classic example of far horizon thinking.

In 1996, Munger presented a thought experiment: how would you turn $2 million in 1884 into $2 trillion by 2034?

Munger’s method began not by charging forward, but by inverting the problem. Instead of asking, “How do we build a giant business?” he asked, “What conditions must be true for a business to compound into trillions?” Working backwards, he presented a clear path: you’d need a universally consumed product, protected by brand power, scalable across geographies, and reinforced by psychology.

Coca-Cola checked every box. Humans everywhere drink water - about 64 ounces per day. If Coke could flavor just a quarter of that intake and capture half the market, the math pointed to trillions in value. From there, Munger layered in psychology: operant conditioning (sugar, caffeine, cold refreshment), Pavlovian association (Coke linked with joy, beauty, and togetherness), and social proof (monkey-see, monkey-do consumption). Adding distribution and trademark protection sealed the moat.

Crucially, Munger also inverted to identify what not to do: don’t allow copycat brands to dilute the trademark, don’t trigger consumer backlash with abrupt changes (see: New Coke), and don’t cheapen the product’s quality. By systematically eliminating failure points, the path to compounding became increasingly robust.

Munger’s lesson is a masterclass in Terminal State. Whether investing, building, or tackling life’s puzzles, forward thinking alone isn’t enough. The biggest insights often come from working backwards from the desired outcome - identifying the non-negotiables, the failure modes, and the lollapalooza effects that emerge when multiple forces combine.

The 1% IRR: The power of dual perspectives

The strength of Terminal State lies not in replacing intrinsic value analysis, but in complementing it.

Intrinsic Value enforces discipline;

Terminal State enforces perspective.

Together, they form a powerful toolkit: intrinsic valuation keeps you honest about today, while Terminal State thinking keeps you honest about tomorrow.

[1] Credit to Fred Losen for pressing this point.